Ushabti: Servants Who Worked For Their Owners In Afterlife In Ancient Egyptian Beliefs

A. Sutherland - AncientPages.com - Ushabti were servants devoted to working for their deceased owners. In ancient Egyptian religion, the tombs were equipped with small-sized and mummy-shaped figurines with arms crossed on the chest. The use of them was widespread, and their 'mission' was to set the deceased free from the necessity of labor in the afterlife.

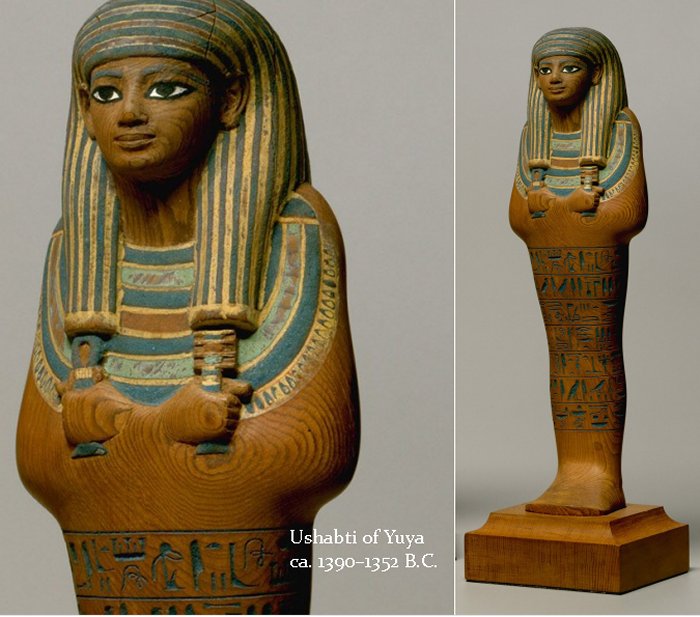

Shabti of Yuya. As the parents of Queen Tiye, wife of Amenhotep III, Yuya and Tjuyu were granted burial in the Valley of the Kings. They were provided with funerary equipment from the finest royal workshops, as demonstrated by this wonderfully carved shabti, on which even the knees are indicated in detail. The text on the figurine states that the shabti will substitute for the spirit in any necessary and obligatory tasks it is called upon to perform in the afterlife. (New Kingdom: the 18th Dynasty, reign of Amenhotep III. Date: ca. 1390–1352 BC. image source

Shabti of Yuya. As the parents of Queen Tiye, wife of Amenhotep III, Yuya and Tjuyu were granted burial in the Valley of the Kings. They were provided with funerary equipment from the finest royal workshops, as demonstrated by this wonderfully carved shabti, on which even the knees are indicated in detail. The text on the figurine states that the shabti will substitute for the spirit in any necessary and obligatory tasks it is called upon to perform in the afterlife. (New Kingdom: the 18th Dynasty, reign of Amenhotep III. Date: ca. 1390–1352 BC. image source

Depending on the tomb, the number of ushabtis varied; some had beautiful form and rich, full of details decoration, especially when made of enamel, applied by ancient Egyptians to stone objects, pottery, and sometimes even jewelry.

Sometimes, early ushabtis were made of wax, but most often, clay and wood were used in their production. Later figurines were usually made of much more resistant and durable materials like stone, terracotta, metal, glass, and most frequently, glazed earthenware known as the Egyptian faience (blue-green glazed ushabtis).

While ushabtis manufactured for the rich were often miniature works of art, however, the significant quantities of discovered ushabti figurines were the result of cheap artistry, based on single molds with a few details, only. Archaeologists frequently discovered boxes full of ill-shaped and uninscribed porcelain figures buried in the tombs with the dead.

These small workers were stored, but always ready to answer the call of the gods to work in the next world for the owner of the tomb.

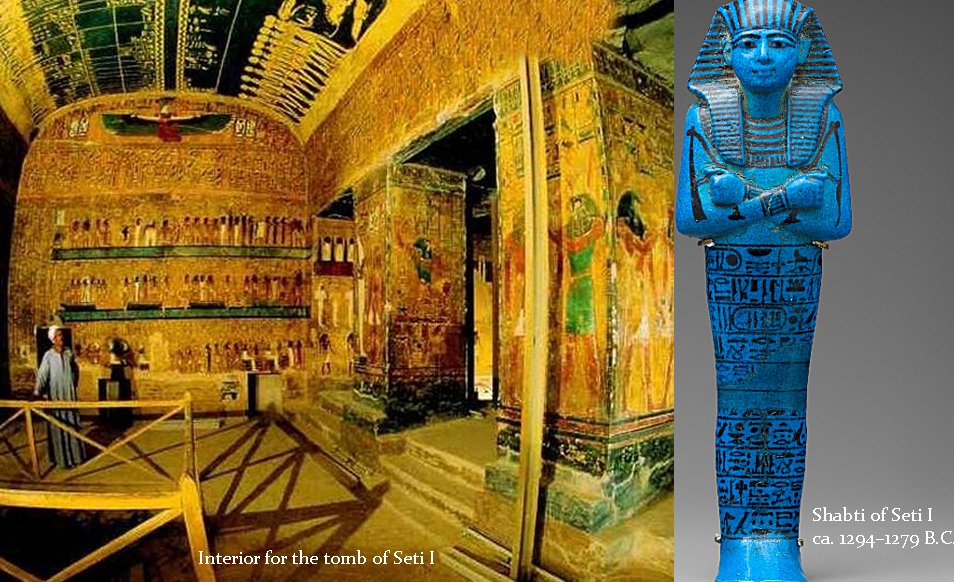

This ushabti was one of the hundreds made for the pharaoh Seti I, the father of Ramesses II. Shabtis were placed in a tomb so the owner's spirit would not have to perform manual labor in the afterlife.

This ushabti was one of the hundreds made for the pharaoh Seti I, the father of Ramesses II. Shabtis were placed in a tomb so the owner's spirit would not have to perform manual labor in the afterlife.

The use of the ushabti figures continued down to the Roman period and the tradition was widespread. Over the centuries, the number and quality of these artifacts changed. In the early Middle Kingdom, it was common to place two pieces of carefully made figurines in the grave. Later, in the Late period, ancient Egyptians decided that the deceased needed many more workers who accompanied them to the afterlife, and it was not uncommon to put up to one thousand of these artifacts in a tomb.

During the 18th Dynasty of Thutmose IV, they began to be fashioned as servants with sacks, baskets, and agriculture tools. With such equipment, the ushabti-workers could magically replace the dead owner when the gods requested him to undertake physical work such as irrigation and cultivation of fields, clearing irrigation channels, etc.

Even royal ushabtis were often depicted holding a hoe or a pick and carrying a basket on shoulders.

The ushabtis were usually covered with texts, and included in grave equipment from the Middle Kingdom (21st-18th centuries BC) to the Ptolemaic period (332–30 BC). During the New Kingdom (1539–1075 BC), the figurines were made to resemble the tomb's owner, and were fashioned in the form of a mummy, bearing the owner’s name.

It is said that in the tomb of Seti I, king of Egypt about 1370 BC no less than seven hundred wooden ushabtis were found inscribed with the 6th Chapter of the Book of the Dead, and covered with bitumen, which was used by ancient Egyptians to embalm mummies.

Written by – A. Sutherland - AncientPages.com Senior Staff Writer

Copyright © AncientPages.com All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed in whole or part without the express written permission of AncientPages.com

Expand for referencesReferences:

Brier B, Hobbs H., Daily Life of The Ancient Egyptians

A. Wallis Budge, Egyptian Magic

More From Ancient Pages

-

DNA From 3,800-Year-Old Individuals Sheds New Light On Bronze Age Families

Archaeology | Aug 29, 2023

DNA From 3,800-Year-Old Individuals Sheds New Light On Bronze Age Families

Archaeology | Aug 29, 2023 -

Qilin – One Of Four Noble Animals In Chinese Myths And Legends

Chinese Mythology | Jan 26, 2021

Qilin – One Of Four Noble Animals In Chinese Myths And Legends

Chinese Mythology | Jan 26, 2021 -

Artifacts From King Henry VIII’s Warship The Mary Rose – Analyzed

Archaeology | Apr 28, 2020

Artifacts From King Henry VIII’s Warship The Mary Rose – Analyzed

Archaeology | Apr 28, 2020 -

Fin Folk – Mythical Amphibious Sea People On Orkney And Shetland

Featured Stories | Feb 22, 2016

Fin Folk – Mythical Amphibious Sea People On Orkney And Shetland

Featured Stories | Feb 22, 2016 -

LIDAR Will ‘Map’ The Ground Surface To Reveal New Picture Of Ancient Native American Culture

Archaeology | Aug 18, 2023

LIDAR Will ‘Map’ The Ground Surface To Reveal New Picture Of Ancient Native American Culture

Archaeology | Aug 18, 2023 -

Shishak (Sheshonq I): Egyptian King Who Invaded Judah And United Egypt

Featured Stories | Feb 28, 2019

Shishak (Sheshonq I): Egyptian King Who Invaded Judah And United Egypt

Featured Stories | Feb 28, 2019 -

King Alaric’s Strange Dream, Sack Of Rome And Forever Hidden Grave

Featured Stories | Oct 29, 2020

King Alaric’s Strange Dream, Sack Of Rome And Forever Hidden Grave

Featured Stories | Oct 29, 2020 -

Strzyga (Strix): Slavic Malevolent Winged Female Demon With Two Souls That Usually Haunts Churches, Towers, Barns

Featured Stories | Aug 9, 2019

Strzyga (Strix): Slavic Malevolent Winged Female Demon With Two Souls That Usually Haunts Churches, Towers, Barns

Featured Stories | Aug 9, 2019 -

Intriguing Hoard Of Bronze Age Bracelets From Brittany, France Remains An Archaeological Puzzle

Featured Stories | Jan 30, 2024

Intriguing Hoard Of Bronze Age Bracelets From Brittany, France Remains An Archaeological Puzzle

Featured Stories | Jan 30, 2024 -

Greek God Asclepius And Ancient Healing Center ‘Asclepion Of Pergamum’

Civilizations | Nov 29, 2014

Greek God Asclepius And Ancient Healing Center ‘Asclepion Of Pergamum’

Civilizations | Nov 29, 2014 -

Unique 2,500-Year-Old Celtic Jewelry – Oldest Iron Age Gold Treasure Ever Found In Britain

Archaeology | Mar 3, 2017

Unique 2,500-Year-Old Celtic Jewelry – Oldest Iron Age Gold Treasure Ever Found In Britain

Archaeology | Mar 3, 2017 -

Unusual Ancient Human Bones Found In A Grave In Derbyshire – Burial Place Of A Legendary Person?

Featured Stories | Apr 24, 2024

Unusual Ancient Human Bones Found In A Grave In Derbyshire – Burial Place Of A Legendary Person?

Featured Stories | Apr 24, 2024 -

Remarkable Underground City Of Nushabad: A Masterpiece Of Ancient Architecture

Ancient Technology | Nov 17, 2015

Remarkable Underground City Of Nushabad: A Masterpiece Of Ancient Architecture

Ancient Technology | Nov 17, 2015 -

Ancient Temple Dedicated To God Zeus Discovered In Sinai, Egypt

Archaeology | Apr 26, 2022

Ancient Temple Dedicated To God Zeus Discovered In Sinai, Egypt

Archaeology | Apr 26, 2022 -

Restorations At Stratonicea Ancient City Of Gladiators In Turkish Muğla Province

Archaeology | May 10, 2023

Restorations At Stratonicea Ancient City Of Gladiators In Turkish Muğla Province

Archaeology | May 10, 2023 -

Full Moon In Ancient Myths And Legends Of Our Ancestors

Featured Stories | Nov 14, 2016

Full Moon In Ancient Myths And Legends Of Our Ancestors

Featured Stories | Nov 14, 2016 -

Magnificent Trumpington Cross And Highly Unusual Anglo-Saxon ‘Bed Burial’ In Cambridge Offer Unique Insight Into English Christianity

Archaeology | Feb 22, 2018

Magnificent Trumpington Cross And Highly Unusual Anglo-Saxon ‘Bed Burial’ In Cambridge Offer Unique Insight Into English Christianity

Archaeology | Feb 22, 2018 -

Controversial Discovery : 15,000 Ancient Ebla Tablets Prove Old Testament To Be Accurate

Archaeology | Oct 5, 2015

Controversial Discovery : 15,000 Ancient Ebla Tablets Prove Old Testament To Be Accurate

Archaeology | Oct 5, 2015 -

Dismantled Ancient Stone Circle In West Wales Was Used To Rebuilt As Stonehenge

Archaeology | Feb 13, 2021

Dismantled Ancient Stone Circle In West Wales Was Used To Rebuilt As Stonehenge

Archaeology | Feb 13, 2021 -

Ancient DNA Reveals: Iberian Males Were Almost Completely Replaced Between 4,500 And 4,000 Years Ago

Archaeology | Mar 15, 2019

Ancient DNA Reveals: Iberian Males Were Almost Completely Replaced Between 4,500 And 4,000 Years Ago

Archaeology | Mar 15, 2019