Ancient Greeks Reached Iceland Before The Vikings – New Theory Suggests

Ellen Lloyd - AncientPages.com - The problem with researching Iceland's ancient history is the lack of written sources.

Most scholars say Iceland was discovered by Norse people who created the first settlement on the island around 870–930. The island was not populated until the Viking Age.

The oldest written document is the Íslendingabók (The Book of the Icelanders), written about 1130. Another interesting source dated to the 12th century is Landnámabók (The Book of Settlements).

The Icelandic Book of Settlements states Norwegian Ingólfr Arnarson was the first permanent settler who reached the island in 874. He built a home for himself and his wife, Hallveig Fródadóttir, at a site named Reykjavík. He worked as a farmer when more than 400 settlers sailed to Iceland with their families, servants, and enslaved people to claim part of the land. Most of the settlers came from Norway, but some came from other Nordic countries and the Norse Viking Age settlements in the British Isles.

Icelandic Sagas contain many fascinating stories about how sailors and settlers reached the island. However, these events are often associated with prophecies and supernatural powers making it hard to determine what did take place at the time.

For example, in Icelandic Sagas, we can read about many voyages to Iceland that "are purposeful, quasi-supernatural events, often guided by prophecies that are made before the settles even set off for Iceland." 1

One journey in the Vatnsdæla saga from 1300 A.D. focuses on Ingemund (Ingimundr Þorsteinsson), who fought for King Harald Fairhair of Norway at the Battle of Hafrsfjord.

More and more scholars have become interested in the possibility that ancient Greeks reached Iceland long before the Vikings and Norse people. This theory is based on the writings of Pytheas of Massilia (350 B.C. – 285 B.C.), who described his voyage to the Arctic and reported a strange land in the North today referred to as Thule.

"Pytheas was a Greek geographer, explorer, and astronomer. Today, he is considered the first known scientist who visited and described the Arctic, polar ice, and the Celtic and Germanic tribes. Being a good astronomer, Pytheas was also the first person to provide the world with a description of the Midnight Sun.

The accounts of Pytheas were for centuries discredited, but the idea of Thule captured the imagination of many who longed to learn more about this mysterious land in the North.

"Since classical times, Thule marked the imaginative horizon of the unknown North, first described by Pytheas of Massalia, who in the third century B.C. reported on a strange place far north ('six days sail north of Orcades') where the sun would never set in the summer and where the ocean was solid frozen. Nobody knows for sure how far north Pytheas went himself and how much he relied on secondary knowledge in his own (lost) descriptions of this place." 2

Pytheas stated Thule was inhabited by people whom he called the Hyperboreans. He also said they live on an island in the North of Britannia. It is a place "beyond the north wind." Later Greek and Roman authors such as Pliny, Pindar, and Herodotus described the Hyperboreans as happy people with exceptionally long lifespans and without illness.

The location of Thule has remained a mystery. Could Thule have been Shetlands Faroes, or was the island nothing but a myth?

Based on a new linguistic understanding of the Greek name, Andrew Breeze, an epigrapher at the University of Pamplona, argues the famous Thule was instead Iceland.

"While the name Thule has no meaning in Greek, Breeze suggests that it could be a scribal error for the original name Thymele, which means "altar" in ancient Greek. This name could perfectly fit the southern coast of Iceland." 3

Norsemen landing in Iceland. Painting by Oscar Wergeland (1909). Credit: Public Domain

According to Breeze, clues to the mystery can be found if we picture what Pytheas thought when he first saw Iceland.

In an article published by The Housman Society Journal, Breeze presents his theory arguing that "the dark volcanic cliffs of the south coast (above beaches of black sand) would have an altar's slab-like appearance; and the resemblance would be the more significant if mist and clouds rising from the island (to say nothing of plumes from its volcanoes, several in its southern part) reminded Pytheas of an altar's reeking sacrifices.

If he called the island 'altar, the altar' or thymele, no surprise.

Unfortunately, his wonder (and perhaps awe) on coming across land previously unknown was lost on his scribes. Hence, it seems, the corruption over three centuries from Thymele to Thoule and Thyle and Thule." 4

"Picturing Iceland as a giant altar also fits well with what we know of ancient Greek altars, according to Breeze. Many of these altars were incredibly large, with the one at Pergamum being 40 feet tall, and one at Syracuse was said to have been 600 feet long." 3

Breeze argues that "there can be no doubt that the place discovered by Pytheas was Iceland. An impressive achievement. Other candidates can be dismissed.

He called it Θυμέλη or Thymele' altar (island)' from its resemblance to a temple's sacrificial altar. Erroneous and meaningless 'Thule' can be dismissed as the result of scribal corruption. There is no justification for it, any more than for 'Boadicea' in Tacitus, a queen rightly called Boudica' victorious one, she who is triumphant.'

Nevertheless, anyone familiar with the ways of scholarship can be sure that, just as we still hear of 'Boadica,' so also we shall hear of 'Thule' for years to come. It will be one of the many scribal monsters which disfigure editions of classical texts, histories of the ancient world, and reference books published by famous universities." 4

The possibility ancient Greeks visited Iceland long before the Norsemen is fascinating, and equally are the linguistic arguments presented by Breeze. Unfortunately, no archaeological evidence supports this theory, but maybe one day, scientists will find something speaking in favor of this concept.

Written by - Ellen Lloyd AncientPages.com

Updated on January 14,2024

Copyright © AncientPages.com All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed in whole or part without the express written permission of AncientPages.com

Expand for referencesReferences:

- Barraclough, E. R. (2012). Sailing the Saga Seas: Narrative, Cultural, and Geographical Perspectives in the North Atlantic Voyages of the Íslendingasögur. Journal of the North Atlantic, 18, 1–12.

- Hastrup, Kirsten. "Ultima Thule: Anthropology and the Call of the Unknown." The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute13, no. 4 (2007): 789-804.

- Nathan Steinmeyer - Who Discovered Iceland?, Biblical Archaeology

- Andrew Breeze, Thule and Juvenal xv 112 - The Housman Society Journal, Journal Vol.46, 2020

More From Ancient Pages

-

Archaeologists Encounter A 1,500-Year-Old Mystery In Kent, UK

Archaeology | Mar 16, 2022

Archaeologists Encounter A 1,500-Year-Old Mystery In Kent, UK

Archaeology | Mar 16, 2022 -

3,000-Year-Old Stone Scarab Seal Depicting A Pharaoh Discovered In Israel

Archaeology | Dec 2, 2022

3,000-Year-Old Stone Scarab Seal Depicting A Pharaoh Discovered In Israel

Archaeology | Dec 2, 2022 -

On This Day In History: The Mongol Conqueror Genghis Khan Died – On August 18, 1227

News | Aug 18, 2016

On This Day In History: The Mongol Conqueror Genghis Khan Died – On August 18, 1227

News | Aug 18, 2016 -

Secret Passageways And Caves Beneath Nottingham Castle

Featured Stories | Dec 6, 2015

Secret Passageways And Caves Beneath Nottingham Castle

Featured Stories | Dec 6, 2015 -

Yet Another Beautiful Roman Mosaic In Hatay, Turkey

Archaeology | Jul 14, 2022

Yet Another Beautiful Roman Mosaic In Hatay, Turkey

Archaeology | Jul 14, 2022 -

Ancient Indian Text Re-Writes History Of Number Zero And Mathematics

Archaeology | Sep 15, 2017

Ancient Indian Text Re-Writes History Of Number Zero And Mathematics

Archaeology | Sep 15, 2017 -

Intriguing Ancient ‘Horoscope’ Scroll Found In The Judean Desert

Artifacts | Apr 2, 2024

Intriguing Ancient ‘Horoscope’ Scroll Found In The Judean Desert

Artifacts | Apr 2, 2024 -

Did Human Nature’s Dark Side Help Us Spread Across The World?

Archaeology | Nov 25, 2015

Did Human Nature’s Dark Side Help Us Spread Across The World?

Archaeology | Nov 25, 2015 -

Mysterious Advanced Underground Civilization And A Secret Society – Dangerous Knowledge And Verdict – Part 3

Featured Stories | Apr 24, 2018

Mysterious Advanced Underground Civilization And A Secret Society – Dangerous Knowledge And Verdict – Part 3

Featured Stories | Apr 24, 2018 -

Still Intact 460-Year-Old Bow Found Underwater In Alaska Baffles Scientists – Where Did It Come From?

Archaeology | Mar 17, 2022

Still Intact 460-Year-Old Bow Found Underwater In Alaska Baffles Scientists – Where Did It Come From?

Archaeology | Mar 17, 2022 -

Ancient Feneos excavations: defensive walls, five towers, sanctuary unearthed

Civilizations | Aug 23, 2015

Ancient Feneos excavations: defensive walls, five towers, sanctuary unearthed

Civilizations | Aug 23, 2015 -

Bastet: Protector And Punisher – She Was Among The Most Majestic Egyptian Deities

Egyptian Mythology | Jun 21, 2019

Bastet: Protector And Punisher – She Was Among The Most Majestic Egyptian Deities

Egyptian Mythology | Jun 21, 2019 -

Why Is This Centaur Head A Scientific Mystery?

Archaeology | Jan 19, 2024

Why Is This Centaur Head A Scientific Mystery?

Archaeology | Jan 19, 2024 -

Ancient Maya Lessons On Surviving Drought – Examined By Scientists

Archaeology | Jan 5, 2022

Ancient Maya Lessons On Surviving Drought – Examined By Scientists

Archaeology | Jan 5, 2022 -

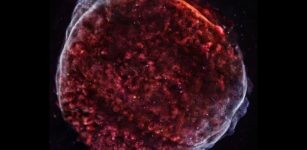

On This Day In History: Supernova Observed In Constellation Lupus By Chinese And Egyptians – On May 1, 1006 AD

News | May 1, 2016

On This Day In History: Supernova Observed In Constellation Lupus By Chinese And Egyptians – On May 1, 1006 AD

News | May 1, 2016 -

Florida’s Windover Bog Bodies Predate The Egyptian Pyramids And Can Rewrite Ancient American History

Featured Stories | Jun 3, 2021

Florida’s Windover Bog Bodies Predate The Egyptian Pyramids And Can Rewrite Ancient American History

Featured Stories | Jun 3, 2021 -

Archaeologists Reveal 12 Exciting Finds From The Gjellestad Viking Ship Dig

Archaeology | May 28, 2022

Archaeologists Reveal 12 Exciting Finds From The Gjellestad Viking Ship Dig

Archaeology | May 28, 2022 -

Cheng I Sao: Dangerous Female Pirate Whose Strict Code Of Laws Kept Pirates Subordinated And Successful

Featured Stories | Mar 11, 2019

Cheng I Sao: Dangerous Female Pirate Whose Strict Code Of Laws Kept Pirates Subordinated And Successful

Featured Stories | Mar 11, 2019 -

On This Day In History: ‘Sea King’ Ragnar Lodbrok Seizes Paris – On March 28, 845

Featured Stories | Mar 28, 2016

On This Day In History: ‘Sea King’ Ragnar Lodbrok Seizes Paris – On March 28, 845

Featured Stories | Mar 28, 2016 -

DNA From Mysterious Hominin In China Suggests Native Americans’ East Asian Roots

Archaeology | Jul 14, 2022

DNA From Mysterious Hominin In China Suggests Native Americans’ East Asian Roots

Archaeology | Jul 14, 2022