Dolmen de Soto: Unique Millennia-Old Underground Structure Remains A Puzzling Enigma

A. Sutherland - AncientPages.com - Among the more than two hundred megalithic structures discovered in southwestern Spain's province of Huelva, there is one particularly impressive and, at the same time, mysterious and puzzling.

Dolmen de Soto in Spain. Credit: Diario de Huelva

Dolmen de Soto in Spain. Credit: Diario de Huelva

A giant millennia-old underground structure known as Dolmen de Soto, buried beneath a mound 60 meters in diameter, is often referred to as Spain's underground Stonehenge and one of the most extensive circular megalithic arrangements in Spain.

Its ancient history is fascinating, and thanks to modern techniques, scientists have discovered ancient drawings on the stones and many display figures armed with daggers, staffs, and axes. Interestingly, based on the investigation of Dolmen de Soto, no other single megalithic structure in Europe contains so many well-armed figures.

So the question is: Were these ancient people frightened of someone or something?

What Was The Purpose Of Dolmen de Soto?

Recent archaeological excavations also revealed and documented the existence of a Neolithic stone circle with a diameter of 65 m that now dates to 5,000-4,000 BC.

Inside Dolmen De Soto. Credit: IAPH

The circle's building was created of stones varying in size and shape. An underground passage, measuring 21.5 meters, starts narrow and then extends to three meters in width and height as it reaches the back of the monument. Inside, a gallery consists of 63 stone pillars, a frontal slab, and 30 other stones covering it.

What was the purpose of Dolmen de Soto? Was this great megalith a sanctuary for the cult of death? Or perhaps it was a place of reverence of important gods and other divinities?

Was it a graveyard? If so, why were only a few people buried in this big underground complex? How was it constructed? There are many questions, but not all of them have clear answers.

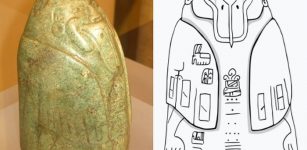

As many as 69 granite pillars - dated between 3000 and 2500 BC - line the walls. The Dolmen has an anthropomorphic stele with a human face, belt, and trident, similar to the Dolmen on the Channel Island of Guernsey.

The structure was discovered and excavated by Armando de Soto in 1923. Hugo Obermaier investigated its architecture, an enormous quantity of engravings, and various stelae used more than once.

The underground structure of the long corridor dolmens family is the most extensive megalithic facility in the Huelva province. It is almost 21m long (ca 69ft), though its width varies from 0,82m at the door up to 3.10m (10ft).

Inside the mound, experts found a metalworking workshop dating back to 3,000 BC, indicating that the weapons' drawings are most probably related to the discovery of metallurgy.

Additionally, the researchers discovered only eight bodies buried in seven different places inside the Dolmen. The bodies appear crouched near the wall and have orthostats (large rock boulders, known as uprights) decorated with a few engravings showing the image of the deceased, his protecting totemic sign, or some of his weapons.

Today, we know much about Dolmen de Soto (also known as Soto Dolmen), but still, much is missing. Doubtful, the mystery of this significant Neolithic landmark will be solved even with modern techniques.

The problem is that the eight bodies buried in seven different places inside the Dolmen are missing!

The bodies and belongings were taken from Dolmen de Soto and transported to the United Kingdom. Their whereabouts are unknown.

Dolmen de Soto, Trigueros. Image credit: Hostal Ciudad Trigueros - CC BY-SA 4.0

Professor of prehistory Mimi Bueno-Ramírez, at Alcalá de Henares University in Madrid, was right, saying: "if we had access to the ancient bodies found at the site, we could learn more about this fascinating place. It's a pity these human remains and artifacts were never analyzed."

A part of Dolmen De Soto's history was lost.

Paintings Engravings Drawings And Symbols

Dolmen de Soto contains a rich collection of painting with symbolic motifs and engravings created with the help of various engraving techniques like incision, low relief, abrasion, and picking.

This rock art is our ancestors' artistic manifestations of cosmology, visions of the world and sky with stars, sun, and moon. Inside Dolmen de Soto, these observations and concepts are expressed through symbols.

Some symbols tell stories about rituals linked to death and the afterlife because they helped them connect the material world with the spirits. Other characters in the Dolmen are related to beliefs, myths, and legends.

As we do today, our ancestors also pondered the concept of possible life after death or whether death ends their existence and represents the gateway to an afterlife.

Dolmen de Soto resembles Stonehenge, and the same ancient builders constructed those structures to a certain degree.

Did Stonehenge look like the Dolmen de Soto? Maybe there is no connection between these two prehistoric sites, but these are questions worth pondering for a curious mind seeking answers.

Written by – A. Sutherland - AncientPages.com Senior Staff Writer

Updated on November 26, 2022

Copyright © AncientPages.com All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed in whole or part without the express written permission of AncientPages.com

Expand for referencesJosé Antonio Linares Catela, ”El dolmen de Soto. Una construcción megalítica monumental de la Prehistoria Reciente de la Península Ibérica”

More From Ancient Pages

-

Silver Coins Hidden In Chess Figure Date Back To Ivan The Terrible’s Days – Discovery In Moscow

Archaeology | May 13, 2017

Silver Coins Hidden In Chess Figure Date Back To Ivan The Terrible’s Days – Discovery In Moscow

Archaeology | May 13, 2017 -

85 Beautiful And Rare Coptic Textiles – A Gift To Museum At Queens College

Archaeology | Apr 4, 2017

85 Beautiful And Rare Coptic Textiles – A Gift To Museum At Queens College

Archaeology | Apr 4, 2017 -

Strange Mummies Of Venzone: Ancient Bodies That Never Decompose Remain An Unsolved Mystery

Featured Stories | Oct 22, 2018

Strange Mummies Of Venzone: Ancient Bodies That Never Decompose Remain An Unsolved Mystery

Featured Stories | Oct 22, 2018 -

World-Famous Temple Of Bel In Palmyra, Syria – Digitally Reconstructed

News | Aug 22, 2020

World-Famous Temple Of Bel In Palmyra, Syria – Digitally Reconstructed

News | Aug 22, 2020 -

Ancient Cosmic Secrets – Mystery Of The ‘Four Sons Of Horus’ And Their Connection To Stars In The Ursa Major Constellation

Featured Stories | Apr 1, 2025

Ancient Cosmic Secrets – Mystery Of The ‘Four Sons Of Horus’ And Their Connection To Stars In The Ursa Major Constellation

Featured Stories | Apr 1, 2025 -

On This Day In History: Malcolm III, King of Scots Died – On Nov 13, 1093

News | Nov 13, 2016

On This Day In History: Malcolm III, King of Scots Died – On Nov 13, 1093

News | Nov 13, 2016 -

First Scandinavian farmers were far more advanced than previously thought

News | Aug 23, 2015

First Scandinavian farmers were far more advanced than previously thought

News | Aug 23, 2015 -

Solar Cult Complex In The Temple Of Hatshepsut In Deir El-Bahari Reconstructed

Archaeology | Mar 2, 2015

Solar Cult Complex In The Temple Of Hatshepsut In Deir El-Bahari Reconstructed

Archaeology | Mar 2, 2015 -

Complete Neolithic Cursus Discovered On Isle of Arran, Scotland

Archaeology | Sep 7, 2023

Complete Neolithic Cursus Discovered On Isle of Arran, Scotland

Archaeology | Sep 7, 2023 -

Remarkable Discovery Of A 19th-Century Boat Buried Under A Road In St. Augustine, Florida

Archaeology | Oct 16, 2023

Remarkable Discovery Of A 19th-Century Boat Buried Under A Road In St. Augustine, Florida

Archaeology | Oct 16, 2023 -

Ukko: Karelian-Finnish God Of Thunderstorms, Harvest, Patron Of Crops And Cattle

Featured Stories | Apr 2, 2020

Ukko: Karelian-Finnish God Of Thunderstorms, Harvest, Patron Of Crops And Cattle

Featured Stories | Apr 2, 2020 -

Celtiberians: Intriguing Martial Culture And Their Skilled Warrior Infantry

Civilizations | Jul 13, 2024

Celtiberians: Intriguing Martial Culture And Their Skilled Warrior Infantry

Civilizations | Jul 13, 2024 -

Strange Tuxtla Statuette And Its Undeciphered Inscription – An Epi-Olmec Puzzle

Artifacts | Mar 14, 2018

Strange Tuxtla Statuette And Its Undeciphered Inscription – An Epi-Olmec Puzzle

Artifacts | Mar 14, 2018 -

Cyrus The Great: Founder Of Achaemenid Empire Who Conquered Medians, Lydians And Babylonians

Featured Stories | Mar 21, 2019

Cyrus The Great: Founder Of Achaemenid Empire Who Conquered Medians, Lydians And Babylonians

Featured Stories | Mar 21, 2019 -

Modern Humans Carrying The Neanderthal Variant Have Less Protection Against Oxidative Stress

Archaeology | Jan 6, 2022

Modern Humans Carrying The Neanderthal Variant Have Less Protection Against Oxidative Stress

Archaeology | Jan 6, 2022 -

Is This The World’s Oldest Joke?

Featured Stories | Feb 21, 2014

Is This The World’s Oldest Joke?

Featured Stories | Feb 21, 2014 -

Controversial ‘Anomaly’ Discovered On Mount Ebal Could Be Biblical Joshua’s Altar

Biblical Mysteries | Apr 6, 2020

Controversial ‘Anomaly’ Discovered On Mount Ebal Could Be Biblical Joshua’s Altar

Biblical Mysteries | Apr 6, 2020 -

Rare 1,000 Year-Old Crusader-Era Bird Pendant Discovered

Archaeology | Mar 28, 2023

Rare 1,000 Year-Old Crusader-Era Bird Pendant Discovered

Archaeology | Mar 28, 2023 -

Ancient Petroglyphs In Toro Muerto Are Not What We Thought – Archaeologists Say

Archaeology | May 24, 2024

Ancient Petroglyphs In Toro Muerto Are Not What We Thought – Archaeologists Say

Archaeology | May 24, 2024 -

On This Day In History: Battle Of Lagos Took Place Between Royal Navy Of Britain and France – On August 19, 1759

News | Aug 19, 2016

On This Day In History: Battle Of Lagos Took Place Between Royal Navy Of Britain and France – On August 19, 1759

News | Aug 19, 2016