Intriguing Genetics: First Ancient Irish Human Genomes – Sequenced

AncientPages.com - A team of geneticists from Trinity College Dublin and archaeologists from Queen’s University Belfast have sequenced the genomes of an early farmer woman, who lived near Belfast some 5,200 years ago, and three men from a later period, around 4,000 years ago in the Bronze Age, after the introduction of metalworking.

These ancient Irish genomes each show unequivocal evidence for massive migration, according to researchers.

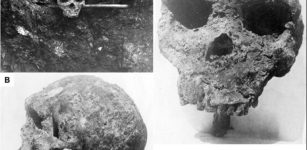

Reconstruction of Ballynahatty Neolithic skull by Elizabeth Black. Her genes tell us she had black hair and brown eyes. Image credit: Barrie Hartwell.

The early farmer has a majority ancestry originating ultimately in the Middle East, where agriculture was invented. The Bronze Age genomes are different with about a third of their ancestry coming from ancient sources in the Pontic Steppe. a vast region of flat grassland extending from the Danube region to the Ural mountains.

Migration has been a hot topic in archaeology. Opinion has been divided on whether the great transitions in the British Isles, from a hunter-gatherer lifestyle to one based on agriculture and later from stone to metal use, were due to local adoption of new ways or whether these influences were derived from influxes of new people.

“There was a great wave of genome change that swept into Europe from above the Black Sea into Bronze Age Europe and we now know it washed all the way to the shores of its most westerly island,” said Professor of Population Genetics in Trinity College Dublin, Dan Bradley, who led the study.

According to Professor Bradley, this degree of genetic change invites the possibility of other associated changes, perhaps even the introduction of language ancestral to western Celtic tongues.

While the early farmer had black hair, brown eyes and more resembled southern Europeans, the genetic variants circulating in the three Bronze Age men from Rathlin Island had the most common Irish Y chromosome type, blue eye alleles and the most important variant for the genetic disease, haemochromatosis – frequent in people of Irish descent.

This discovery is particularly important because it marks the first identification of an important disease variant in prehistory.

“Genetic affinity is strongest between the Bronze Age genomes and modern Irish, Scottish and Welsh, suggesting establishment of central attributes of the insular Celtic genome some 4,000 years ago,” added PhD Researcher in Genetics at Trinity, Lara Cassidy.

Research is published in the international journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

AncientPages.com

source: Trinity College Dublin