Ancient DNA Sheds New Light On The Fall Of Major Civilizations

Jan Bartek - AncientPages.com - Based on previous archaeological studies, researchers know that the Old Kingdom of Egypt and the Akkadian Empire, both Bronze Age civilizations, experienced sudden declines in population several thousand years ago. The cause of the decline has been a subject of debate. During the late 3rd millennium BCE, the Eastern Mediterranean and Near East witnessed societal changes in many regions, usually explained by social and climatic factors.

Knossos palace at Crete, the largest Bronze Age archaeological site on Crete and the ceremonial and political centre of the Minoan civilization and culture. Credit: Adobe Stock - Vladimircaribb

However, a recent archaeogenetic reveals diseases could have been behind the decline. Scientists from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, the British School at Athens, and Temple University have discovered evidence of pathogens in the teeth of individuals from the Bronze Age that could explain why two ancient civilizations failed.

"The plague bacterium Yersinia pestis, which was involved in some of the most destructive historical pandemics, circulated across Eurasia at least from the onset of the 3rd millennium BCE,9, 10, 11, 12, 13 but the challenging preservation of ancient DNA in warmer climates has restricted the identification of Y. pestis from this period to temperate climatic regions. As such, evidence from culturally prominent regions such as the Eastern Mediterranean is currently lacking," the researchers write their study.

Ancient DNA was taken from individuals discovered in the Hagios Charalambos cave, situated on the Lasithi plateau of Crete, Greece. This site is of great archaeological value as it was used by our ancestors as used as a secondary burial site from the Late Neolithic (ca. 4th millennium Before Common Era [BCE]) to the Middle Minoan II period (18th century BCE).

By examining the teeth from the remains of people dated back to approximately 2290 and 1909 B.C., scientists found evidence of a bacteria responsible for two of history's most significant diseases – typhoid fever and plague. Yersinia pestisis the bacteria behind the plague and Salmonella enterica, is the bacteria responsible for typhoid fever.

"The occurrence of these two virulent pathogens at the end of the Early Minoan period in Crete," they wrote in their paper, "emphasizes the necessity to re-introduce infectious diseases as an additional factor possibly contributing to the transformation of early complex societies in the Aegean and beyond."

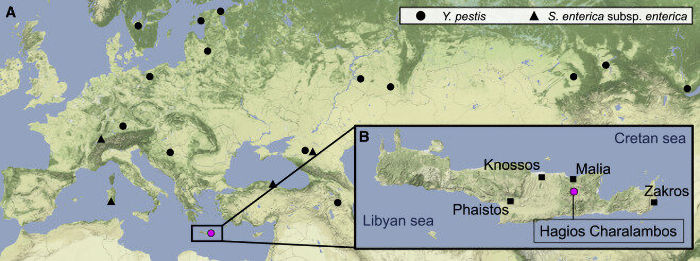

Location of archaeological sites with evidence of Y. pestis and S. enterica subsp. enterica from the LNBA (A) Map of Eurasia indicating relevant LNBA sites with genetic evidence of Y. pestis (circles) and S. enterica subsp. enterica (triangles). Hagios Charalambos in pink, previously published sites in black. (B) Map of Crete showing the location of Hagios Charalambos (pink) and important Bronze Age palatial sites (black). Credit: Current Biology (2022). DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2022.06.094

"Both pathogens, Y. pestis and S. enterica subsp. enterica, which were identified in this study at the site of Hagios Charalambos from this time of transition, can cause severe epidemics in human populations. Y. pestis was responsible for at least three major pandemics in human history: the Justinianic plague, or first pandemic (540/41–750 CE), the Black Death/second pandemic (ca. 1346 until the 18th century CE), and the third pandemic (1855 until mid-20th century CE).

See also: More Archaeology News

Archaeogenetic studies have shown that this pathogen was already present in a wide geographic range between central Europe and Siberia from the Middle Neolithic onward and especially during the Bronze Age," the science team explained in their paper.

The next step is to conduct further genetic studies to determine how widespread such infections may have been.

Written by Jan Bartek - AncientPages.com Staff Writer