Mexico’s Comalapa Cave With Toothless Skulls – Investigation By INAH

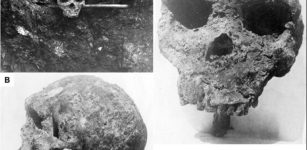

Conny Waters - AncientPages.com - INAH researchers have analyzed approximately 150 toothless skulls and other bones unearthed a decade ago in southeastern Mexico’s Comalapa Cave, in the town of Carrizal, near the border with Guatemala.

These human remains are not related to people killed in recent incidents of violence but correspond to individuals decapitated between 900 and 1200 AD.

The analysis of approximately 150 skulls indicates that these correspond to individuals decapitated between 900 and 1200 AD. C. Photo: Chiapas State Attorney General's Office

Believing to be at the scene of a crime, the researchers collected the bone elements and began their analysis in Tuxtla Gutiérrez, and with the collaboration of the National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH) it was possible to determine that the bones were pre-Hispanic, according to press release by Mexico’s Ministry of Culture.

INAH physical anthropologists informed that the funerary context is about a thousand years old and even theorize that there was an altar of skulls, or tzompantli , in the Comalapa Cave.

The existence of a tzompantli is also supported by the evidence of traces of aligned wooden sticks, according to the record raised in the cave by the then Chiapas State Attorney General's Office in 2012.

Comalapa Cave - location map

According to the physical anthropologist, the fact that the skulls of Comalapa do not have perforations in the parietal and temporal bones is based on the knowledge about altars that used structures to fix the skulls without perforating them.

The Huei tzompantli of Tenochtitlan, on the other hand, was described by Fray Bernardino de Sahagún as "a low platform with "two platforms and a framework of three posts that carry a horizontal bar from which the skulls are suspended, seen from the front, by the temples." Most sacrificial victims had their hearts ripped out, then decapitated, the skull skinned and a spear or rod threaded through the parietal bones and placed in the Tzompantli. It must be clarified that the skulls are not in any way only remains of bodies but deified parts, they are ixiptla, that is, the living image of the god. During the Conquest, the Tzompantli abandoned its place as an offering to the gods, to become a way to intimidate the invaders, both Bernal Díaz del Castillo and Hernán Cortés assured that they saw the heads of their companions in arms with the hair and beards overgrown, and there were even horse heads."

"Many of these structures were made of wood, a material that disappeared over time and could have collapsed all the skulls," he said.

Although long bones of femurs, tibias or radii have been identified, until now not a single complete burial has been recognized but mostly skulls or their fragments of numerous individuals who were beheaded.

“We still do not have the exact calculation of how many there are, since some are very fragmented, but so far we can talk about approximately 150 skulls,” said the specialist, providing a summary of the preventive conservation, cleaning, and cataloging work applied in each one of them.

Together with archaeologists from the INAH Chiapas Center, it has been established that the bone remains of the Comalapa Cave have cranial modifications of the erect tabular type and that they date from the Early Postclassic (900 and 1200 AD).

INAH confirms that 150 skulls found in Chiapas are pre-Hispanic. Source: Chiapas State Attorney General's Office. Image credit: INAH

"We have recognized the skeletal remains of three infants, but most of the bones are from adults and, until now, they are more from women than from men," said the researcher, noting that a common characteristic of the skulls is that none of them preserves the teeth.

Although it has not yet been established whether the teeth were extracted in life or postmortem, experts recognize precedents of this type in Chiapas: the Cueva de las Banquetas, explored in the 1980s by the INAH in the municipality of La Trinitaria , where 124 skulls that did not preserve teeth were recovered.

Another case is the Cueva Tapesco del Diablo, discovered in 1993 by Mexican and French explorers in the municipality of Ocozocoautla. Five skulls were discovered there with the particularity of having been placed on a wooden tapesco (grid).

The physical anthropologist Javier Montes de Paz emphasized the need to continue with the research in the complex, and even carry out new field seasons in the Cueva de Comalapa.

In this sense, he highlighted the responsibility that citizens must have to respect these spaces that were often used for rituals and pointed out that irregular visits affect the archaeological heritage, sometimes irreversibly.

"The call is that when people locate a context that is likely to be archaeological, they avoid intervening and notify the local authorities or the INAH directly," he concluded.

Written by Conny Waters - AncientPages.com Staff Writer