Burtele Foot Fossil Reveals Two Ancient Human Ancestors Lived Side by Side

Jan Bartek - AncientPages.com - Recent discoveries have shed new light on the diversity of ancient human ancestors. The story goes back to 2009, when a team led by Arizona State University paleoanthropologist Yohannes Haile-Selassie uncovered eight foot bones dating back 3.4 million years in Ethiopia’s Afar Rift. This fossil, known as the Burtele Foot, was found at the Woranso-Mille paleontological site and formally announced in 2012.

Afar rift, Ethiopia. Credit: DavidMPyle - CC BY-SA 4.0, Right top and left - Ancient hominin fossils. Credit: Arizona State University. Image compilation by AncientPages.com

Initially, while some teeth were also discovered nearby, researchers were uncertain whether these remains came from the same sediment layer as the Burtele Foot. In 2015, Haile-Selassie’s team introduced a new species called Australopithecus deyiremeda from this region, but did not immediately assign the Burtele Foot to this species due to lingering doubts about their association.

Evidence That Two Distinct Hominin Species Coexisted In East Africa Around 3.4 Million Years Ago

Over a decade of continued fieldwork has since yielded additional fossils that allow scientists to confidently link the Burtele Foot with Australopithecus deyiremeda. This finding provides compelling evidence that two distinct hominin species coexisted in East Africa around 3.4 million years ago—offering valuable insights into our evolutionary history and highlighting greater diversity among early human ancestors than previously recognized.

"When we found the foot in 2009 and announced it in 2012, we knew that it was different from Lucy's species, Australopithecus afarensis, which is widely known from that time," said Haile-Selassie, director of the Institute of Human Origins (IHO) and a professor in the ASU School of Human Evolution and Social Change.

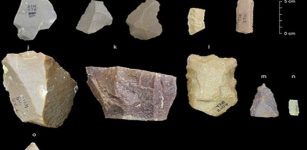

The Burtele Foot with its elements in the anatomical position. Photo by Yohannes Haile-Selassie/ASU

"However, it is not common practice in our field to name a species based on postcranial elements –elements below the neck—so we were hoping that we would find something above the neck in clear association with the foot. Crania, jaws and teeth are usually the elements used in species recognition."

Assigning the Burtele foot to a specific species is just one aspect of a broader discovery. The Woranso-Mille site is of particular importance because it provides the only clear evidence that two related hominin species coexisted in the same place at the same time.

The Burtele foot, attributed to Australopithecus deyiremeda, displays more primitive features compared to the feet of Australopithecus afarensis, the species to which Lucy belonged. Notably, A. deyiremeda retained an opposable big toe—an adaptation useful for climbing trees.

However, on the ground, this hominin walked upright on two legs and likely pushed off with its second toe, unlike modern humans, who push off with their big toes.

"The presence of an abducted big toe in Ardipithecus ramidus was a big surprise because, at 4.4 million-years-ago, there was still an early hominin ancestor which retained an opposable big toe, which was totally unexpected," said Haile-Selassie.

"Then 1-million-years later, at 3.4-million-years ago, we find the Burtele foot, which is even more surprising. This is a time when we see species like A. afarensis whose members were fully bipedal with an adducted big toe. What that means is that bipedality—walking on two legs—in these early human ancestors came in various forms.

"The whole idea of finding specimens like the Burtele foot tells you that there were many ways of walking on two legs when on the ground, there was not just one way until later."

Teeth Reveal Different Diets

To get insight into the diet of A. deyiremeda, Naomi Levin, a professor at the University of Michigan, sampled eight of the 25 teeth found at the Burtele localities for isotope analysis. The process involves cleaning the teeth, making sure to only sample the enamel.

"I sample the tooth with a dental drill and a very tiny (< 1mm) bit—this equipment is the same kind that dentists use to work on your teeth," said Levin. "With this drill, I carefully remove small amounts of powder. I store that powder in a plastic vial and transport it back to our lab at the University of Michigan for isotopic analysis."

Fragments of BRT-VP-2/135 before assembly. The specimen was found in 29 pieces, of which 27 of them were recovered by sifting and picking the sifted dirt. Photo by Yohannes Haile-Selassie/ASU

The results were surprising.

While Lucy's species was a mixed feeder, eating C3 (resources from trees and shrubs) and C4 plants (tropical grasses and sedges), A. deyiremeda was utilizing resources that are more on the C3 side.

"I was surprised that the carbon isotope signal was so clear and so similar to the carbon isotope data from the older hominins A. ramidus and Au. anamensis," said Levin.

"I thought the distinctions between the diet of A. deyiremeda and A. afarensis would be harder to identify, but the isotope data show clearly that A. deyiremeda wasn't accessing the same range of resources as A. afarensis, which is the earliest hominin shown to make use of C4 grass-based food resources."

Another key data analysis was carefully establishing the age of the fossils and understanding the surrounding ancient environment in which the ancient hominins lived in.

"We have done a tremendous amount of careful field work at Woranso-Mille to establish how different fossil layers relate, which is crucial to understanding when and in what settings the different species lived," said Beverly Saylor, professor of earth, environmental and planetary sciences at Case Western Reserve University. Saylor led the geological work that established the stratigraphic association between the foot and Au. deyiremeda.

A Juvenile Jaw

In addition to the 25 teeth discovered at Burtele, Haile-Selassie’s team also uncovered the jaw of a juvenile that, based on dental anatomy, was clearly identified as belonging to A. deyiremeda. According to Gary Schwartz, an IHO research scientist and professor at the School of Human Evolution and Social Change, this jaw contained a complete set of baby teeth in place as well as numerous adult teeth developing within the bone.

Juvenile mandible digital reconstruction from microCT scans. Images in the left column show the jaw’s external details, while images in the right column show the external bone rendered partly transparent to see the adult teeth developing away deep within the bony mandible. Reconstruction by Ragni and Schwartz/Courtesy of Nature.

"For a juvenile hominin of this age, we were able to see clear traces of a disconnect in growth between the front teeth (incisors) and the back chewing teeth (molars), much like is seen in living apes and in other early australopiths, like Lucy's species," said Schwartz.

See also: More Archaeology News

"I think the biggest surprise was, despite our growing awareness of how diverse these early australopith (i.e., early hominin) species were—in their size, in their diet, in their locomotor repertoires and in their anatomy—these early australopiths seem to be remarkably similar in the manner in which they grew up."

Ancient hominins co-existing

Understanding how these ancient ancestors moved and what they ate provides scientists with new insights into how species coexisted without one driving the other to extinction.

"All of our research to understand past ecosystems from millions of years ago is not just about curiosity or figuring out where we came from, said Haile-Selassie. "It is our eagerness to learn about our present and the future as well."

"If we don't understand our past, we can't fully understand the present or our future. What happened in the past, we see it happening today," he said in a press release.

"In a lot of ways, the climate change that we see today has happened so many times during the times of Lucy and A. deyiremeda. What we learn from that time could actually help us mitigate some of the worst outcomes of climate change today."

Written by Jan Bartek - AncientPages.com Staff Writer

Expand for referencesYohannes Haile-Selassie, New finds shed light on diet and locomotion in Australopithecus deyiremeda, Nature (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-025-09714-4. www.nature.com/articles/s41586-025-09714-4

Fred Spoor, Mystery owner of African hominin foot identified, Nature (2025). DOI: 10.1038/d41586-025-03451-4 , doi.org/10.1038/d41586-025-03451-4