Medieval Rich People Unknowingly Poisoned Themselves With Lead And Other Hazardous Heavy Metals

AncientPages.com - A new study suggests that medieval people were exposed to hazardous heavy metals like lead, which was frequently used to glaze pottery. The poor, who could not afford such items, avoided the high levels of exposure.

Being rich in the Middle Ages, had its advantages, but being able to afford expensive and beautiful crockery was not one of them.

"One of the worst side effects of lead is that it leads to lower intelligence in children. After a few generations [of lead consumption] it could become really bad," says co-author Associate Professor Kaare Lund Rasmussen, from the Department of Physics and Chemistry at the University of Southern Denmark.

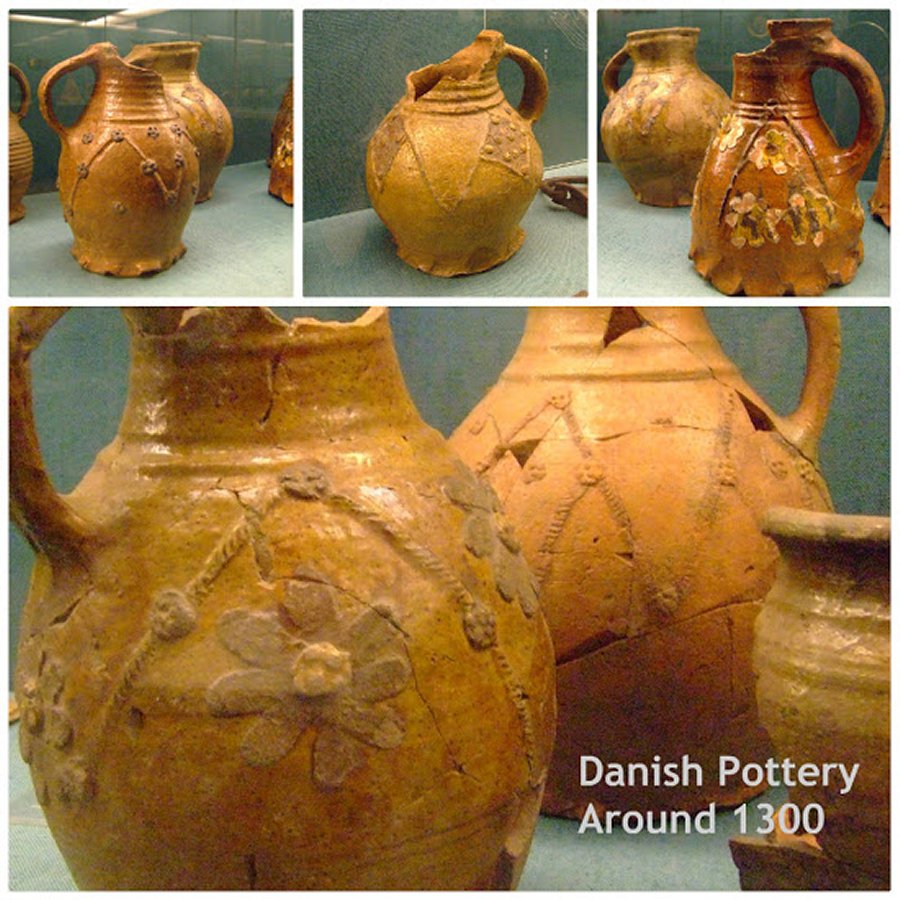

Ancient pottery. Næstved,Sydsjælland

Archaeologist Mikael Manøe Bjerregaard from Odense City Museums in Denmark is full of praise for the new research.

"Although we’ll never have the names of these medieval people, we can still say a lot about their standard of living. It’s fascinating that we can get that close," says Bjerregaard, who was not involved in the study.

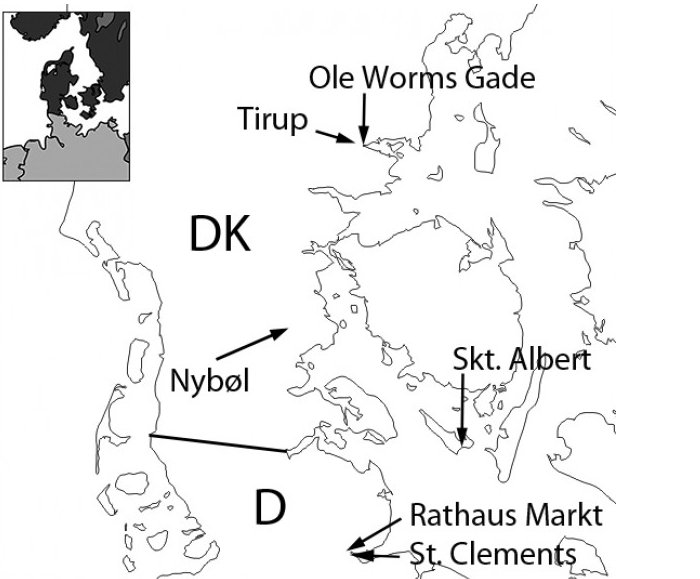

The researchers examined the lead content of 283 skeletons from six cemeteries in Denmark and Germany, dating back to the Middle Ages between 1000 and 1536 CE, and represent both urban and rural communities.

These expensive ceramics were a status symbol for the wealthy urbanites in the Middle Ages, but they also exposed them to dangerous lead poisoning. (Photo (left): Kaare Lund Rasmussen. Photo (right): Birgitte Svennevig)

The researchers compared the lead content in skeletons from the city with those from the country, and saw that city dwellers had significantly higher levels of lead that those living in the country.

The cause, says Bjerregaard , was expensive ceramics decorated with a lead oxide glazing.

"These ceramics were used much less in the countryside, so it’s an urban phenomenon as wealthier people would’ve had greater access to these ceramics. It’s the top of society that would’ve had them, and they would’ve been relatively rare in the countryside," he says.

Danish pottery. Credits: Nationalmuseet, Denmark

Ceramics were glazed with lead oxide to prevent the baked clay from absorbing foods and liquids, which otherwise made them a nightmare to clean.

The lead oxide glaze would coat the inside of the bowl, protecting the clay beneath. And it had an added advantage of being transparent, so a variety of colours could be added for decorative affect.

"However, it has side effects: if you use it for acidic or salty foods then the lead in the surface can be dissolved and leak into the food,” says Rasmussen.

Bjerregaard is not surprised that wealthy people in urban areas were exposed to lead. He believes the findings provide an important perspective that archaeology has not dealt with much before--the health hazards associated with the glazed ceramics.

The map shows the locations of the cemeteries in Denmark and Germany that were used in the study. (Figure: Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports)

"It's partly something that could have been deduced, because there are many crafts that worked with lead. For example lead glazed windows and roofs, which were urban phenomena. But it's exciting that we now have concrete chemical evidence of it," said Bjerregaard.

A combination of chemical analysis and archaeological techniques allowed Rasmussen and colleagues to get this close to medieval culture. By the same method, they also found out that townspeople were exposed to more mercury than their contemporaries in the countryside.

"Traditionally in archaeology we’ve been limited to what we could physically observe, such as broken legs which had healed, blows to the head, and a few diseases that sat on the bones. We couldn’t get any closer than that, but now we can," says Bjerregaard.

The new study is published in the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports.

AncientPages.com

Expand for referencesMore From Ancient Pages

-

King Midas’s Gold Desire Became A Nightmare

Featured Stories | Nov 2, 2023

King Midas’s Gold Desire Became A Nightmare

Featured Stories | Nov 2, 2023 -

A 4.4 Million-Year-Old Hand Of ‘Ardi’ Has Some Clues On Humans’ Upright Walking

Fossils | Feb 25, 2021

A 4.4 Million-Year-Old Hand Of ‘Ardi’ Has Some Clues On Humans’ Upright Walking

Fossils | Feb 25, 2021 -

Surprising Discovery Of Ancient Sarcophagus At Paris’ Notre Dame Cathedral

Archaeology | Mar 16, 2022

Surprising Discovery Of Ancient Sarcophagus At Paris’ Notre Dame Cathedral

Archaeology | Mar 16, 2022 -

Oldest Known Projectile Points In The Americas Discovered In Idaho

Archaeology | Dec 23, 2022

Oldest Known Projectile Points In The Americas Discovered In Idaho

Archaeology | Dec 23, 2022 -

Why Was Louis XIV Called The Sun King?

Ancient History Facts | Jul 11, 2019

Why Was Louis XIV Called The Sun King?

Ancient History Facts | Jul 11, 2019 -

Adorable Village Of The Little People In Connecticut

Featured Stories | Jul 25, 2019

Adorable Village Of The Little People In Connecticut

Featured Stories | Jul 25, 2019 -

Ur-Nammu – Popular And Accomplished Ruler Of Sumer

Civilizations | Oct 31, 2016

Ur-Nammu – Popular And Accomplished Ruler Of Sumer

Civilizations | Oct 31, 2016 -

Ogham: Unique Celtic Alphabet Used By Druids And Abandoned During Christian Era

Featured Stories | Jul 9, 2021

Ogham: Unique Celtic Alphabet Used By Druids And Abandoned During Christian Era

Featured Stories | Jul 9, 2021 -

Ancient Mystery From The Age Of Taurus And The Murdered Astronomer – Overlooked Secret In The North – Part 1

Civilizations | Oct 30, 2019

Ancient Mystery From The Age Of Taurus And The Murdered Astronomer – Overlooked Secret In The North – Part 1

Civilizations | Oct 30, 2019 -

Honey-Collecting In Prehistoric West Africa From 3500 Years Ago – Pottery Examined

Archaeology | Apr 14, 2021

Honey-Collecting In Prehistoric West Africa From 3500 Years Ago – Pottery Examined

Archaeology | Apr 14, 2021 -

Extremely Rare Fossils Of 160-Million-Year-Old Sea Spider And Its Diversity By The Jurassic

Fossils | Aug 22, 2023

Extremely Rare Fossils Of 160-Million-Year-Old Sea Spider And Its Diversity By The Jurassic

Fossils | Aug 22, 2023 -

On This Day In History: Gold Discovery In The Yukon – On August 16, 1896

News | Aug 16, 2016

On This Day In History: Gold Discovery In The Yukon – On August 16, 1896

News | Aug 16, 2016 -

Draupnir: God Odin’s Magical Ring That Could Multiply Itself

Featured Stories | Jul 26, 2017

Draupnir: God Odin’s Magical Ring That Could Multiply Itself

Featured Stories | Jul 26, 2017 -

Mystery Of The Horned Serpent In North America, Mesopotamia, Egypt And Europe

Egyptian Mythology | Dec 7, 2017

Mystery Of The Horned Serpent In North America, Mesopotamia, Egypt And Europe

Egyptian Mythology | Dec 7, 2017 -

Book Of Kells: Illuminated Medieval Manuscript From Monastery On Iona, Scotland

Artifacts | Feb 8, 2018

Book Of Kells: Illuminated Medieval Manuscript From Monastery On Iona, Scotland

Artifacts | Feb 8, 2018 -

4,000-Year-Old Village Mentioned In Ancient Texts Unearthed Near Sacred City Of Varanasi

Archaeology | Mar 13, 2020

4,000-Year-Old Village Mentioned In Ancient Texts Unearthed Near Sacred City Of Varanasi

Archaeology | Mar 13, 2020 -

Alexander The Great And The Prophecy Of The Tree Of The Sun And Moon

Featured Stories | Jun 10, 2019

Alexander The Great And The Prophecy Of The Tree Of The Sun And Moon

Featured Stories | Jun 10, 2019 -

On This Day In History: Hubble Space Telescope Was Launched – On April 24, 1990

News | Apr 24, 2016

On This Day In History: Hubble Space Telescope Was Launched – On April 24, 1990

News | Apr 24, 2016 -

Horses In Florida Did Not Travel Far Distances – New Study Suggests

Archaeology | Jan 3, 2019

Horses In Florida Did Not Travel Far Distances – New Study Suggests

Archaeology | Jan 3, 2019 -

Magnificent Solar Alignment Phenomenon In Abu Simbel – The Sun Illuminates The Face Of Pharaoh Ramses II

Featured Stories | Nov 11, 2020

Magnificent Solar Alignment Phenomenon In Abu Simbel – The Sun Illuminates The Face Of Pharaoh Ramses II

Featured Stories | Nov 11, 2020