Ancient Secrets Of The Damascus Steel – Legendary Metal Used By Crusaders And Other Warriors

Ellen Lloyd - AncientPages.com - When the Crusaders reached the Middle East in the 11th century, they discovered swords made of a metal that could slice a hair in half in mid-air, and yet it was strong enough to strike fear into even the bravest and most persistent warrior.

A shamshir (Persian/Iranian sword with a radical curve. The Royal Armoury, Stockholm, Sweden. Unknown author - LSH 77113 - Public Domain

Knowledge of the legendary metal spread, and it became known to the Europeans as the Damascus steel, named after the capital of Syria. Sometime in the 18th century, the formula for Damascus steel was lost, and the original method for producing Damascus steel remains an ancient secret.

Through the ages, armorers who made swords, shields, and armor were rigidly secretive regarding their method, and the formula of the Damascus steel was only known to a few persons.

Many modern attempts have been made to reproduce the metal, but no one has succeeded due to differences in raw materials and manufacturing techniques.

Damascus Steel And Its Remarkable Characteristics

From around the fourth century A.D., Damascus steel was manufactured in several regional locations. The swords produced with Damascus steel were extraordinary because the blades remained devastatingly sharp through battle after battle.

The Damascus steel gave rise to many legends, such as the ability to cut through a rifle barrel or to cut a hair falling across the blade. According to Dr. Helmut Nickel, curator of the Arms and Armor Division of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, legend had it that the best blades were quenched in "dragon blood."

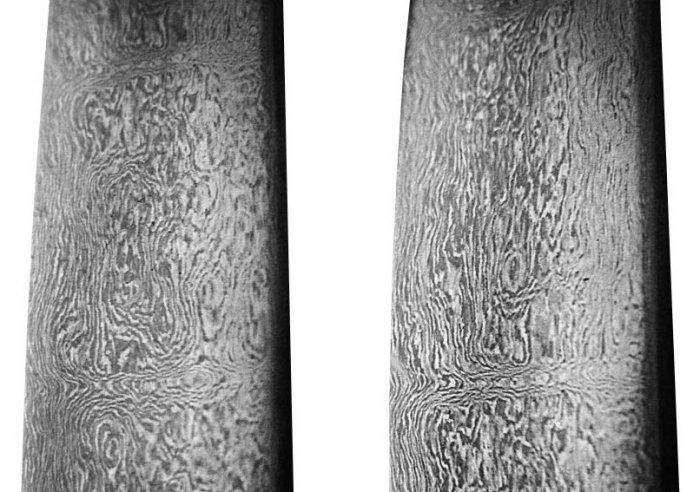

The swords were easily recognized by a characteristic watery or" damask" pattern on their blades." Damascus steel was not only a remarkable feat of engineering but also a thing of aesthetic beauty.

The metal was derived from Wootz, a type of steel originating in India unusually rich in carbon.

Based on archaeological evidence, it has been determined that the production fit the steel started in present-day Tamil Nadu before the start of the Common Era.

Watered pattern on iranian sword blade. Close-up of an 18th-century Persian-forged Damascus steel sword. Image credit: Rahil Alipour Ata Abadi - GFDL

Watered pattern on iranian sword blade. Close-up of an 18th-century Persian-forged Damascus steel sword. Image credit: Rahil Alipour Ata Abadi - GFDL

The Arabs introduced the Indian wootz steel to Damascus, where a weapons industry thrived. Wootz steel was highly prized across several regions of the world over nearly two millennia, and one typical product made of this Indian steel came to be known as the Damascus swords.

From the 3rd century to the 17th century, India was shipping steel ingots to the Middle East.

Lost Knowledge Of The Damascus Steel Formula

By 1750, the production of Damascus swords gradually declined, and the process was lost to metalsmiths.

Why the swords were no longer produced is still a mystery. It has been suggested that Damascus steel production declined because firearms replaced blades, and there was less demand for metal. Another option is that the knowledge of the Damascus steel formula was only known to a small group and thus lost with time. Swordmakers succeeded in concealing their techniques from competitors and posterity.

It is also possible that the trade routes supplying Wootz from India were disrupted or that raw material supplies no longer had the same essential characteristics.

Modern Attempts To Re-Create Damascus Steel

A significant problem in scientific experiments on Wootz Damascus steel is the inability to obtain samples for study. Such a study requires that the blades be cut into sections for microscopic examination, and small quantities must be sacrificed for destructive chemical analysis.

A sword maker of Damascus, Syria. Image source

When researchers at the Technical University of Dresden used X-rays and electron microscopy to examine Damascus steel, they discovered the presence of cementite nanowires and carbon nanotubes. The study showed that these nanostructures are a result of the forging process.

Jeffrey Wadsworth and Oleg D. Sherby, two metallurgists at Stanford University, may have unraveled the mystery of the Damascus steel. According to Dr. Wadsworth, as suspected by several early metallurgists, an essential requirement is a very high carbon content.

Dr. Wadsworth and Dr. Sherby believe it has to be from 1 to 2 percent, compared to only a fraction of 1 percent in ordinary steel. Another critical element in Damascus blade production is forging and hammering at relatively low temperatures - about 1,700 degrees Fahrenheit. After shaping, the blades were reheated to about the same temperature, then rapidly cooled, as by quenching in a fluid.

"Modern Damascus" is made from several types of steel and iron slices welded together to form a billet, and currently, the term "Damascus" (although technically incorrect) is widely accepted to describe modern pattern-welded steel blades in the trade. The patterns vary depending on how the smith works the billet. The billet is drawn out and folded until the desired number of layers is formed. To attain a Master Smith rating with the American Bladesmith Society, it is necessary to forge a Damascus blade with a minimum of 300 layers.

Recreating Damascus steel is a subfield of experimental archaeology. Many have attempted to discover or reverse-engineer the process by which it was made, and several researchers have come a long way, but to completely reproduce the process has so far not been possible.

Damascus steel is, without doubt, magnificent art and cutting-edge technology that may be lost to humankind forever.

Written by Ellen Lloyd – AncientPages.com

Updated on Aug 13, 2023

Copyright © AncientPages.com All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed in whole or part without the express written permission of AncientPages.com

Expand for referencesReferences:

Wes Sander, Intermediate Guide to Bladesmithing

More From Ancient Pages

-

Proof That Neanderthals Ate Crabs 90,000 Years Ago Is Another ‘Nail In The Coffin’ For Primitive Cave Dweller Stereotypes

Archaeology | Feb 7, 2023

Proof That Neanderthals Ate Crabs 90,000 Years Ago Is Another ‘Nail In The Coffin’ For Primitive Cave Dweller Stereotypes

Archaeology | Feb 7, 2023 -

13th Century Black Book Of Carmarthen: Erased Poetry And Ghostly Faces Revealed By UV Light

Artifacts | Apr 4, 2015

13th Century Black Book Of Carmarthen: Erased Poetry And Ghostly Faces Revealed By UV Light

Artifacts | Apr 4, 2015 -

More Than 2,000 Seal Impressions Found In The Ancient City Of Doliche

Archaeology | Nov 24, 2023

More Than 2,000 Seal Impressions Found In The Ancient City Of Doliche

Archaeology | Nov 24, 2023 -

Mystery Of The Black Irish People: Who Were They?

Civilizations | May 24, 2016

Mystery Of The Black Irish People: Who Were They?

Civilizations | May 24, 2016 -

Ivan The Terrible: Military Arsenal Unearthed Near Moscow

Archaeology | Jan 2, 2016

Ivan The Terrible: Military Arsenal Unearthed Near Moscow

Archaeology | Jan 2, 2016 -

Yew: Mysterious Ominous And Sacred Tree Revered By Our Ancestors Since The Dawn Of Civilization

Featured Stories | Feb 8, 2022

Yew: Mysterious Ominous And Sacred Tree Revered By Our Ancestors Since The Dawn Of Civilization

Featured Stories | Feb 8, 2022 -

Manannán Mac Lir – Irish God Of Sea, Healing, Weather And Master Of Shapeshifting

Celtic Mythology | Mar 2, 2023

Manannán Mac Lir – Irish God Of Sea, Healing, Weather And Master Of Shapeshifting

Celtic Mythology | Mar 2, 2023 -

Atacama Desert Reveals More Ancient Secrets

Archaeology | May 8, 2018

Atacama Desert Reveals More Ancient Secrets

Archaeology | May 8, 2018 -

Enigmatic Green Lady In British Folklore

Featured Stories | Jan 9, 2017

Enigmatic Green Lady In British Folklore

Featured Stories | Jan 9, 2017 -

Mysterious Ancient Inscriptions Never Meant To Be Read – Biblical Secrets Revealed

Artifacts | May 17, 2018

Mysterious Ancient Inscriptions Never Meant To Be Read – Biblical Secrets Revealed

Artifacts | May 17, 2018 -

Unravelling The Mystery Of The Yellow Emperor And His Connection To Regulus

Chinese Mythology | Sep 21, 2015

Unravelling The Mystery Of The Yellow Emperor And His Connection To Regulus

Chinese Mythology | Sep 21, 2015 -

Munkholmen: Island With Intriguing Yet Dark And Scary History

Featured Stories | Aug 25, 2023

Munkholmen: Island With Intriguing Yet Dark And Scary History

Featured Stories | Aug 25, 2023 -

On This Day In History: Ruler Of Palenque Yohl Ik’nal Was Crowned – On Dec 23, 583

News | Dec 23, 2016

On This Day In History: Ruler Of Palenque Yohl Ik’nal Was Crowned – On Dec 23, 583

News | Dec 23, 2016 -

Excavation Of A Mysterious 5,000-Year-Old Tomb Linked To King Arthur Has Started

Archaeology | Jul 5, 2022

Excavation Of A Mysterious 5,000-Year-Old Tomb Linked To King Arthur Has Started

Archaeology | Jul 5, 2022 -

Tezcatlipoca: Enigmatic Aztec God Who Looked Inside People’s Hearts And Observed Their Deeds On Earth

Aztec Mythology | Jul 22, 2021

Tezcatlipoca: Enigmatic Aztec God Who Looked Inside People’s Hearts And Observed Their Deeds On Earth

Aztec Mythology | Jul 22, 2021 -

How Norwegians Expressed Resistance Against Nazi Occupation Using Christmas Cards

Featured Stories | Dec 21, 2023

How Norwegians Expressed Resistance Against Nazi Occupation Using Christmas Cards

Featured Stories | Dec 21, 2023 -

Evidence Oldest Bone Spear Point In The Americas Is 13,900 Years Old

Archaeology | Feb 3, 2023

Evidence Oldest Bone Spear Point In The Americas Is 13,900 Years Old

Archaeology | Feb 3, 2023 -

Ancient Stone Ram Figurine – Symbol Of Abundance And Great Courage – Unearthed In Old Cemetery

Archaeology | Oct 2, 2020

Ancient Stone Ram Figurine – Symbol Of Abundance And Great Courage – Unearthed In Old Cemetery

Archaeology | Oct 2, 2020 -

25 Stone Age Caves And Rock Carvings Found In Odisha, India

Archaeology | Mar 30, 2017

25 Stone Age Caves And Rock Carvings Found In Odisha, India

Archaeology | Mar 30, 2017 -

Birth Of Good And Evil In Iroquois Beliefs

Featured Stories | Sep 23, 2019

Birth Of Good And Evil In Iroquois Beliefs

Featured Stories | Sep 23, 2019