Goddesses Of Fate And Destiny In Greek, Roman And Slavic Mythologies

A. Sutherland - AncientPages.com - An Italian humanist philosopher of the early Renaissance, Giovanni Pico della Mirandola (1463-1494), said that the human being is the master of his own life because human nature is a repository of instruments by which each individual can shape their life.

Rodzanice, narczniki, sudiczki - in the Slavic religion, invisible spirits or deities of fate. Generally mentioned in number three, but sometimes mentioned in number four, five, seven or even nine, of which one was "queen". Image credit: Marek Hapon, 2015 - CC BY-SA 4.0

However, those who oppose this belief say that human life results from fate's action - the final and irreversible will of the higher powers. There is no choice; fate is unavoidable, and it is simply our destiny, followed by the end of everything, which means - death.

Throughout the ages, myths and legends about fate have reflected our beliefs. People have often wondered about fate and its power.

The idea of a person's fate being spun was widely known in ancient Europe.

Three mythological goddesses known as "Fates" (with many names in respective languages) represent a common motif in European beliefs. Ancient people respected the idea of a person's fate being spun by divine beings.

According to Norse beliefs, the Norns were responsible for fate. They spun the thread of life at the roots of the World Ash, Yggdrasil.

"The Parcae," ca. 1885) by Alfred Agache. Image via wikipedia

Greek myths and legends make it clear that our attempts to outmaneuver an unavoidable fate are pointless. To the Greeks, fate and its influence on human life were of great concern, and countless myths and texts describe them as ugly older women, sometimes with disabilities.

Their fate goddesses were the Moirai/Moerae (sometimes called 'daughters of the night'), who sprang for each mortal. It is said that they were concerned with death but later began to decide what must happen to individuals.

They may have originated as birth goddesses, also concerned with death, but they later acquired their reputation as agents of destiny and those who control the Threads of Fate.

The Moerae sisters are known as Clotho ("the spinner"), who spins the thread of life, Lachesis ("the allotter or 'drawer of lots'), who assigns each person's destiny and Atropos ("the inevitable"), with scissors in her hands, decides when to snip the thread of life at its end.

They were worshipped as goddesses, and it is said that brides in Athens offered them locks of hair, and women swore by them. The Moirai were independent, and Zeus and other gods, as well as men, had to submit to them.

In Roman mythology, the Parcae (the equivalent of the Moirai) were the female goddesses of destiny. They were usually depicted as women weaving a tapestry covered with men's destinies.

Like the Norse and Greek goddesses of fate, they exercised the same arts. One was busy spinning the yarn, another was drawing out the thread, and another was cutting it.

The three Parcae sisters - Nona, Decima, and Morta - controlled the thread of life of every mortal and immortal from birth to death. Both gods and humans feared their unlimited power.

In the mythology of Slavic people, the Sudice (known after different names among the ancient Slavs) were responsible for the fates and destiny of humanity. They judged and meted out fortune and fatality.

They could appear as a single goddess or as three sisters at the birth of a child, just in time, when a newborn's fortune was foretold and destiny was sealed. The oldest of the sisters spoke last; her words could never be revoked or contradicted.

Fate was determined for all, regardless of whether they were good or wrong.

The Sudice were beautiful old women with white skin and white clothes. They wore necklaces of gold and silver, white kerchiefs, and sometimes carried lit candles. The ancient Slavs made offerings to them in the form of bread, candles, and salt.

Written by – A. Sutherland AncientPages.com Staff Writer

Updated on March 28, 2024

Copyright © AncientPages.com All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed in whole or part without the express written permission of AncientPages.com

Expand for referencesReferences:

Gieysztor Aleksander, Mitologia Słowian

Cotterell, A. A Dictionary of World Mythology

Monaghan P. Encyclopedia of Goddesses and Heroines

Tanner, Ross. Greek Mythology:

More From Ancient Pages

-

Ancient Mystery Of The Menorah – Enigmatic Sacred Object With Complex History

Featured Stories | Nov 5, 2018

Ancient Mystery Of The Menorah – Enigmatic Sacred Object With Complex History

Featured Stories | Nov 5, 2018 -

1,000-Year-Old Bone Skate Found In Moravian City Of Přerov, Czech Republic

Archaeology | Mar 20, 2024

1,000-Year-Old Bone Skate Found In Moravian City Of Přerov, Czech Republic

Archaeology | Mar 20, 2024 -

Tower Of The Winds And Daydreaming Of Andronicus Of Cyrrhus

Featured Stories | May 14, 2019

Tower Of The Winds And Daydreaming Of Andronicus Of Cyrrhus

Featured Stories | May 14, 2019 -

Takshashila: Renowned Learning Center That Attracted Buddhist Masters, Disciples And Students Of The World

Featured Stories | Sep 13, 2021

Takshashila: Renowned Learning Center That Attracted Buddhist Masters, Disciples And Students Of The World

Featured Stories | Sep 13, 2021 -

Binary Code Was Used In Ancient India And Polynesia Long Before Leibnitz Invented It

Ancient Technology | Sep 28, 2017

Binary Code Was Used In Ancient India And Polynesia Long Before Leibnitz Invented It

Ancient Technology | Sep 28, 2017 -

Cryptic North American Blythe Intaglios Reveal The Creator Of Life: Who Was This Unknown Being?

Featured Stories | Aug 23, 2014

Cryptic North American Blythe Intaglios Reveal The Creator Of Life: Who Was This Unknown Being?

Featured Stories | Aug 23, 2014 -

Mysterious Balochistan Sphinx Has An Ancient Story To Tell – But Is An Advanced Ancient Civilization Or Mother Nature Hiding Behind The Story?

Featured Stories | Feb 3, 2018

Mysterious Balochistan Sphinx Has An Ancient Story To Tell – But Is An Advanced Ancient Civilization Or Mother Nature Hiding Behind The Story?

Featured Stories | Feb 3, 2018 -

2500-Year-Old Objects Made From Goat Bones Discovered In Turkey’s City Of Aigai

Archaeology | Sep 17, 2020

2500-Year-Old Objects Made From Goat Bones Discovered In Turkey’s City Of Aigai

Archaeology | Sep 17, 2020 -

There Is Evidence Humans Reached North America 130,000 Years Ago – Archaeologist Says

Archaeology | Mar 28, 2022

There Is Evidence Humans Reached North America 130,000 Years Ago – Archaeologist Says

Archaeology | Mar 28, 2022 -

On This Day In History: Canute – Cnut The Great – Danish King Of England Died – On Nov 12, 1035

Featured Stories | Nov 12, 2016

On This Day In History: Canute – Cnut The Great – Danish King Of England Died – On Nov 12, 1035

Featured Stories | Nov 12, 2016 -

On This Day In History: Alexander The Great Defeats Darius III Of Persia In The Battle Of The Granicus On May 22, 334 B.C.

News | May 22, 2016

On This Day In History: Alexander The Great Defeats Darius III Of Persia In The Battle Of The Granicus On May 22, 334 B.C.

News | May 22, 2016 -

Mag Mell: Irish Tradition Of Otherworldly Paradise That Could Be Reached Through Death And Glory

Celtic Mythology | Feb 26, 2019

Mag Mell: Irish Tradition Of Otherworldly Paradise That Could Be Reached Through Death And Glory

Celtic Mythology | Feb 26, 2019 -

Mysterious Ancient People Who Mastered Thought-Transmission Through Space And Spoke At Distance

Featured Stories | Apr 26, 2021

Mysterious Ancient People Who Mastered Thought-Transmission Through Space And Spoke At Distance

Featured Stories | Apr 26, 2021 -

Secrets Of The Bible: Codex Zacynthius – Hidden Text In New Testament May Soon Be Uncovered

Biblical Mysteries | Oct 7, 2014

Secrets Of The Bible: Codex Zacynthius – Hidden Text In New Testament May Soon Be Uncovered

Biblical Mysteries | Oct 7, 2014 -

Moon: What Was Its Role In Beliefs Of Ancient People?

Featured Stories | Apr 6, 2019

Moon: What Was Its Role In Beliefs Of Ancient People?

Featured Stories | Apr 6, 2019 -

Fire – Powerful Symbol That Played A Key Role In History Of Mankind

Ancient Symbols | May 29, 2020

Fire – Powerful Symbol That Played A Key Role In History Of Mankind

Ancient Symbols | May 29, 2020 -

Rare Collection Of Roman Coins Unearthed In Ancient City Of Aizanoi, Turkey

News | Feb 4, 2021

Rare Collection Of Roman Coins Unearthed In Ancient City Of Aizanoi, Turkey

News | Feb 4, 2021 -

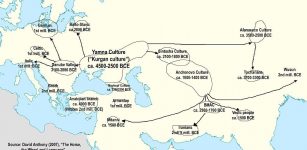

Mystery Of Ancient Language PIE From Which Half Of All Languages Originate

Featured Stories | Apr 3, 2017

Mystery Of Ancient Language PIE From Which Half Of All Languages Originate

Featured Stories | Apr 3, 2017 -

Three 1850-Year-Od Stone Ossuaries Prevented From Looting Near Kafr Kanna In Galilee

Archaeology | Jun 21, 2023

Three 1850-Year-Od Stone Ossuaries Prevented From Looting Near Kafr Kanna In Galilee

Archaeology | Jun 21, 2023 -

Rare Minoan Sealstone Is A Miniature Masterpiece Unearthed In 3,500-Year-Old Tomb Of Powerful Mycenaean Warrior

Archaeology | Nov 8, 2017

Rare Minoan Sealstone Is A Miniature Masterpiece Unearthed In 3,500-Year-Old Tomb Of Powerful Mycenaean Warrior

Archaeology | Nov 8, 2017