Herculaneum Time Capsule: Ancient Scrolls With Secrets Buried Under Volcanic Ash And Stones

A. Sutherland - AncientPages.com - On the morning of August 24, 79 AD, Mount Vesuvius erupted and broke its centuries-long silence. Its great cloud of hot ash, stones, and poisonous gases completely buried the whole Roman city of Pompeii and for more than seventeen centuries, it would remain lost, forgotten, sealed, and preserved in a time capsule.

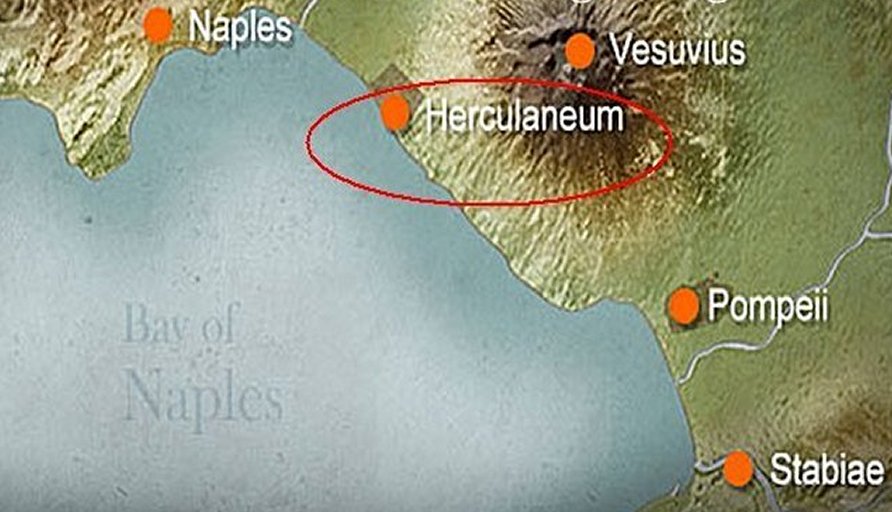

Vesuvius also completely buried another Roman town - Herculaneum, on the coast of south-west Italy.

In 79 AD, Vesuvius erupted and completely buried the Roman cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum, on the coast of southwest Italy. For a long time, both cities have remained forgotten, sealed, and preserved in a time capsule.

The origin of Herculaneum is not clear. The city's name is based on the demi-god Hercules, who founded the city, according to legend. It may have been a Greek settlement but the early town also shows evidence of Etruscan influence. Herculaneum is another time capsule keeping old secrets buried under volcanic ash and stones.

Because the large depth of covering deposits discouraged looting more artifacts have survived. Excavations resulted in the discovery of not only fabrics and even food, but also a roll of papyrus.

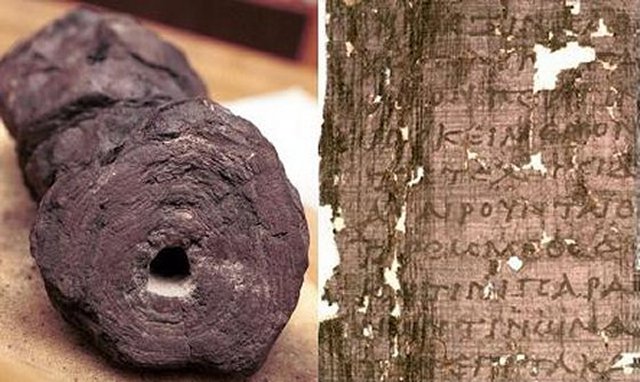

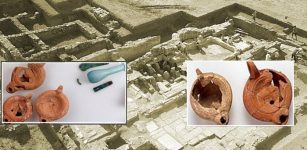

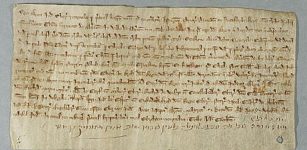

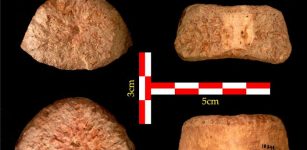

The papyri were blackened cylinders (pictured below) more akin to 'lumps of coal' and at first they were a mystery to the excavators. On examining some broken fragments, however, it was discovered that the cylinders were indeed scrolls containing Greek text written on scorched papyrus. Credits: Photography by Brian Donovan, The University of Auckland - Centre for Academic Development. Herculaneum Conservation Project

"The British Museum's 2013 show of artifacts from the Roman cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum, buried in ash during an explosive eruption of Mount Vesuvius, was a sell-out. But could even greater treasures - including lost works of classical literature - still lie underground?

For centuries scholars have been searching for the lost works of ancient Greek and Latin literature. In the Renaissance, books were found in monastic libraries. In the late 19th Century papyrus scrolls were found in the sands of Egypt, and in Herculaneum was found an entire library from the ancient Mediterranean. Excavations of the Herculaneum's area are difficult because diggings must reach beneath approximately 20 meters of concrete-like material, the hardened volcanic mud which covered it for almost 2,000 years.

In 1752 workers tunneling into a large, wealthy villa (later known as "Villa of the Papyri") discovered a large number of what appeared to be sticks of charcoal, some of them bundled together. Upon closer inspection, these sticks proved to be rolls of the ancient writing material papyrus. Numerous attempts to open these rolls and read their contents failed, due to their extreme fragility and the fact that they were burnt by the ca. 300 degree Celsius volcanic flow, compressed by the weight of rubble and mud, and congealed by water," we read on The Philodemus Project's website.

Eventually, several hundred of the rolls were partly cut apart and partly unrolled.

A conservator from the Vatican, Father Antonio Piaggio (1713-1796), devised a machine to delicately open the scrolls. But it was slow work - the first one took around four years to unroll. And the scrolls tended to go to pieces.

The fragments pulled off by Piaggio's machine were fragile and hard to read. "They are as black as a burnt newspaper," says Dr Dirk Obbink, an American-born papyrologist, classicist, specializing in the history of religion and its texts and a lecturer in Papyrology at Oxford University.

Under normal light the charred paper looks "a shiny black" says Obbink, while "the ink is a dull black and sort of iridesces".

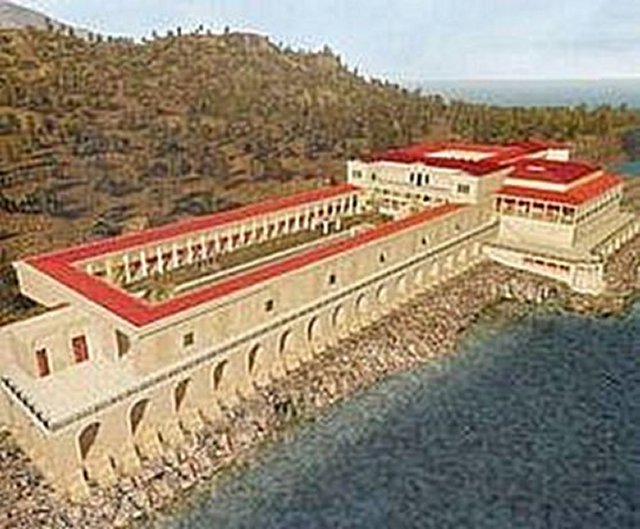

The Villa of the Papyri at Herculaneum contained many papyrus scrolls, carbonized in the eruption but otherwise still intact.

Reading it is "not very pleasant", he adds. In fact, when Obbink first began working on them in the 1980s the difficulty of the fragments was a shock. On some pieces, the eye can make out nothing. On others, by working with microscopes and continually moving the fragments to catch the light in different ways, a few letters can be made out.

In 1999, scientists from Brigham Young University in the US examined the papyrus using infrared light. Deep in the infrared range, at a wavelength of 700-900 nanometres, it was possible to achieve a good contrast between the paper and the ink.

Letters began to jump out of the ancient papyrus. Instead of black ink on black paper, it was now possible to see black lines on a pale grey background.

In 2008, a further advance was made through multi-spectral imaging. Instead of taking a single ("monospectral") image of a fragment of papyrus under infrared light (at typically 800 nanometres) the new technology takes 16 different images of each fragment at different light levels and then creates a composite image.

The villa, believed to have been owned by the father-in-law of Julius Caesar, Lucius Calpurnius Piso Caesoninus, stretched for more than 250m along the shoreline. It would appear that it was originally built in the first century BC, as a formal atrium villa, subsequently extended. Only eight columns of the portico have been excavated, but judging from the plan of the house there must have been four additional columns to the east of the entrance. Copyright: Photography by Brian Donovan, The University of Auckland - Centre for Academic Development. Copyright © 2001-2009, Herculaneum Conservation Project.

With this technique, Obbink is seeking not only to clarify the older infrared images but also to look again at fragments that previously defied all attempts to read them. The detail of the new images is so good that the handwriting on the different fragments can be easily compared, which should help reconstruct the lost texts out of the various orphan fragments. "The whole thing needs to be redone," says Obbink.

But many of the texts that have emerged so far are written by a follower of Epicurus (341 BC - 270 BC), the philosopher and poet Philodemus of Gadara (c.110-c.40/35BC).

Not the entire unique library of the Villa of the Papyri in Herculaneum has been unrolled. The damage - caused by the eruption lasted 18 hours - destroyed the artifacts. Could it be possible to read them in some way, for example - virtually?

In 2009 two unopened scrolls from Herculaneum belonging to the Institut de France in Paris were placed in a Computerised Tomography (CT) scanner, normally used for medical imaging.

The machine, which can distinguish different kinds of bodily tissue and produce a detailed image of a human's internal organs could potentially be used to reveal the internal surfaces of the scroll.

"We were able to unwrap a number of sections from the scroll and flatten them into 2D images - and on those sections, you can clearly see the structure of the papyrus: fibers, sand," says Dr. Brent Seales, a computer science professor at the University of Kentucky, who led the effort.

Totally, about 2,000 scrolls have been recovered from the villa, of which almost 1,700 have been unrolled.

"The villa remains one of the great buildings of the ancient world and it should certainly be excavated," according to Robert Fowler, professor of Greek and dean of arts at Bristol University.

With certainty, there is much more hidden underground.

Written by – A. Sutherland AncientPages.com Staff Writer

Copyright © AncientPages.com All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed in whole or part without the express written permission of AncientPages.com

More From Ancient Pages

-

Unknown Saxon Village And Bronze Age Artifacts Found Near Ely, Cambridgeshire

Archaeology | Sep 18, 2023

Unknown Saxon Village And Bronze Age Artifacts Found Near Ely, Cambridgeshire

Archaeology | Sep 18, 2023 -

Long-Lost Legendary Ancient Temple Discovered On San Miguel Hill In Mexico

Archaeology | Oct 20, 2023

Long-Lost Legendary Ancient Temple Discovered On San Miguel Hill In Mexico

Archaeology | Oct 20, 2023 -

Why Didn’t Pythagoras And His Followers Eat Beans?

Ancient History Facts | Jan 18, 2019

Why Didn’t Pythagoras And His Followers Eat Beans?

Ancient History Facts | Jan 18, 2019 -

World’s First Diva Was Livia – Wife Of Emperor Augustus

Ancient History Facts | Aug 2, 2016

World’s First Diva Was Livia – Wife Of Emperor Augustus

Ancient History Facts | Aug 2, 2016 -

Are The Mysterious ‘Ubeidiya Limestone Spheroids Of Early Hominins Evidence Of Intentional Symmetric Geometry?

Archaeology | Sep 6, 2023

Are The Mysterious ‘Ubeidiya Limestone Spheroids Of Early Hominins Evidence Of Intentional Symmetric Geometry?

Archaeology | Sep 6, 2023 -

History Shows: Taxes And Bureaucracy Are Cornerstones Of Democracy

Archaeology | Feb 18, 2021

History Shows: Taxes And Bureaucracy Are Cornerstones Of Democracy

Archaeology | Feb 18, 2021 -

Neanderthals Painted Andalusia’s Cueva de Ardales – New Study Confirms Their Cave Art

Archaeology | Aug 3, 2021

Neanderthals Painted Andalusia’s Cueva de Ardales – New Study Confirms Their Cave Art

Archaeology | Aug 3, 2021 -

Massive Ancient Fortifications Reveal Poznan Was Poland’s First Capital

Archaeology | Jul 2, 2020

Massive Ancient Fortifications Reveal Poznan Was Poland’s First Capital

Archaeology | Jul 2, 2020 -

Mysterious Ancient People Who Mastered Thought-Transmission Through Space And Spoke At Distance

Featured Stories | Apr 26, 2021

Mysterious Ancient People Who Mastered Thought-Transmission Through Space And Spoke At Distance

Featured Stories | Apr 26, 2021 -

Advanced Heating System Discovered In Ruins Of Metropolis ‘City Of Mother Goddess’

Archaeology | Nov 17, 2019

Advanced Heating System Discovered In Ruins Of Metropolis ‘City Of Mother Goddess’

Archaeology | Nov 17, 2019 -

Bartolomeo Colleoni: Most Respected Mercenary General Of The 15th Century Italy

Featured Stories | Sep 10, 2019

Bartolomeo Colleoni: Most Respected Mercenary General Of The 15th Century Italy

Featured Stories | Sep 10, 2019 -

What Was The Medieval Shame Flute?

Ancient History Facts | Jan 27, 2020

What Was The Medieval Shame Flute?

Ancient History Facts | Jan 27, 2020 -

York’s Thriving Medieval Jewish Community – New Study

Archaeology | Aug 22, 2023

York’s Thriving Medieval Jewish Community – New Study

Archaeology | Aug 22, 2023 -

Wax Tablets Reveal Ancient Secrets of The Illyrians

Artifacts | Sep 5, 2015

Wax Tablets Reveal Ancient Secrets of The Illyrians

Artifacts | Sep 5, 2015 -

1.5 Million-Year-Old Human Vertebra Discovered In Israel’s Jordan Valley Sheds New Light On Migration From Africa To Eurasia

Archaeology | Feb 3, 2022

1.5 Million-Year-Old Human Vertebra Discovered In Israel’s Jordan Valley Sheds New Light On Migration From Africa To Eurasia

Archaeology | Feb 3, 2022 -

Surprising Inscription Discovered On Birka Ring – Ancient Viking Artifact

Archaeology | May 13, 2015

Surprising Inscription Discovered On Birka Ring – Ancient Viking Artifact

Archaeology | May 13, 2015 -

Pliska: Ancient City Ahead Of Its Time With Secret Underground Tunnels, Sewage And Heating Systems

Featured Stories | May 22, 2017

Pliska: Ancient City Ahead Of Its Time With Secret Underground Tunnels, Sewage And Heating Systems

Featured Stories | May 22, 2017 -

66 Diorite Statues Of Lion-Headed Goddess Sekhmet Discovered In Luxor, Egypt

Archaeology | Mar 9, 2017

66 Diorite Statues Of Lion-Headed Goddess Sekhmet Discovered In Luxor, Egypt

Archaeology | Mar 9, 2017 -

13th Century Black Book Of Carmarthen: Erased Poetry And Ghostly Faces Revealed By UV Light

Artifacts | Apr 4, 2015

13th Century Black Book Of Carmarthen: Erased Poetry And Ghostly Faces Revealed By UV Light

Artifacts | Apr 4, 2015 -

Extraordinary Fossils From The End Of The Age Of The Dinosaurs – Study

Paleontology | Oct 15, 2023

Extraordinary Fossils From The End Of The Age Of The Dinosaurs – Study

Paleontology | Oct 15, 2023